Topiarism

(Note: this week's text initiates a series of occasional pieces of short fiction, relating-- however distantly at times-- to art, art making, artists, and the intersection of such things with Modern Life as we know it.)

The first time I saw them was in his apartment in Detroit. He was just starting out then, writing human-interest pieces for the Journal. He had this tiny studio on the fifth floor of an old brick building, and he wanted there to be something living when he came home at night. He couldn’t deal with the responsibility of even so much as a goldfish, so he had these things in pots, out on the fire escape where they could get some sun.

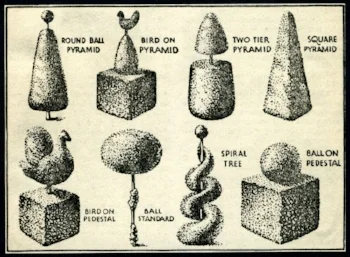

They looked pretty funny, to tell the truth, and I told him that I didn’t understand why he had them. Even a vase of dried weeds would be nicer. He just laughed and told me that these stunted bushes were his little art project—a miniaturized version of his Southern California boyhood. Now, from the distance of time and a considerable number of miles, he remembered all that structured shrubbery with nostalgic fondness. John didn’t have pets. Instead, he had topiary.

They were still skinny and pretty young back then- three, maybe four years old, since he’d started them when he got his first job- but over time they really shaped up. The paper moved him around pretty often, but I wasn’t able to stay in one place (or at one job) very long either, so I got to see those shrubs in a lot of places: Seattle, Dallas, Philadelphia, Chicago. By Dallas, the collection had a kind of sharp-edged denseness that reminded me of those fuzzy dice that people hang from their rear-view mirrors. Although I had grudgingly come to admire them all, my favorite one was the size and shape of a regulation football.

(I even saw them once in John’s old hometown, LA, where he had rented a bungalow up near the Hollywood Bowl. Thinking that the climate was at last just right, he had put them outside along the walk, but the neighborhood dogs kept mistaking them for fireplugs. By the time I passed through, they were back indoors, recovering from the ordeal of frequent exposure to dog urine.)

I got married around then and even bought a home, thinking that it might help tie me down, but John kept on moving. I lost track of him after I gave up the house and just about everything else in the divorce. A few years later, I managed to get promoted to New York right before Christmas. On a whim, I called the paper to see where John was working, and amazingly enough, he was right there in the office. He gave me his home address and told me to meet him there after work. I felt kind of funny about it—it was Christmas Eve, for one thing—but I didn’t have anywhere else to go. And, apparently, neither did he.

It was the kind of loft that no artist will ever live or work in. A big, lonely room, punctuated with marooned islands of furniture. John seemed OK, if a little tired. He was smaller than I remembered, or maybe that was just because the place was so undefined. He went into the kitchen part of it to get some glasses and ice while I strolled around.

I guess unconsciously I was looking for them, but when I circled the sofa and saw them in the shadows, it was still quite a shock. They were dead, beyond a reasonable doubt. Even I could tell that and I’m lousy with plants, though their branches still made those interesting, unnatural shapes: cube, football, pointy little cone.

He came over and saw me looking at them. I tried to make a joke about surviving urban life, but he just shook his head. Much later, after most of a bottle of scotch, he said that they had died sometime back. He didn’t know why. Still, he hadn’t had the heart to leave them behind since, after all (I remember this part very clearly) they were a perfect reminder of how nothing could really live that way. By then, it was much too late to ask him exactly what he meant.

1 LIKE